Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 40:48 — 36.3MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS | More

Trust in journalism. Still complicated. Do we value connection over logic? Are we persuadable? What is the mix of facts, context, opinions? Learn from Joy Mayer

Blog subscribers: Listen to the podcast here. Scroll down through show notes to read the post.

Episode Notes

Prefer to read, experience impaired hearing or deafness?

Find FULL TRANSCRIPT at the end of the other show notes or download the printable transcript here

Contents with Time-Stamped Headings

to listen where you want to listen or read where you want to read (heading. time on podcast xx:xx. page # on the transcript)

Introducing Joy Mayer and Trusting News 01:46. 1

Trust is complicated (where have we heard that before?) 06:18. 3

Affective versus cognitive trust – connection or logic 09:31. 3

Persuadable but overwhelmed 11:03. 4

Engaging transparency 11:54. 4

Self-aware before convincing 14:08. 5

Opinion without context. Facts with context. 15:48. 5

Earning trust even if wrong 19:58. 7

Transparently confusing 26:38. 8

Person first – meeting us where we are. Where are we? 27:59. 9

Falling off the cliff of trust 34:10. 11

Please comments and ask questions

- at the comment section at the bottom of the show notes

- on LinkedIn

- via email

- DM on Instagram or Twitter to @healthhats

Credits

The views and opinions presented in this podcast and publication are solely the responsibility of the author, Danny van Leeuwen, and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

Music by permission from Joey van Leeuwen, Drummer, Composer, Arranger

Web and Social Media Coach Kayla Nelson @lifeoflesion

Inspiration from Josh Richardson, Jodyn Platt, Laura Marcial, Aaron Carroll, Barry Blumenfeld, Lynne Becker

Links

From Joy Mayer

- A UF project I’m loosely affiliated with that did research into how to make vaccine communication effective: https://covid19vaccinescommunicationprinciples.org/

- A deck my team updates periodically, collecting research on trust in news: http://bit.ly/trustingnewsresearch

- Advice I wrote for an industry publication about how to consume news responsibly: https://www.poynter.org/ethics-trust/2020/how-to-consume-news-during-the-coronavirus-pandemic/

Healthcare Triage– Aaron Carroll’s YouTube channel

Related podcasts and blogs

Trust is Complicated: Person-First Safe Living in a Pandemic Part 3

About the Show

Welcome to Health Hats, learning on the journey toward best health. I am Danny van Leeuwen, a two-legged, old, cisgender, white man with privilege, living in a food oasis, who can afford many hats and knows a little about a lot of healthcare and a lot about very little. Most people wear hats one at a time, but I wear them all at once. We will listen and learn about what it takes to adjust to life’s realities in the awesome circus of healthcare. Let’s make some sense of all this.

To subscribe go to https://health-hats.com/

Creative Commons Licensing

The material found on this website created by me is Open Source and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution. Anyone may use the material (written, audio, or video) freely at no charge. Please cite the source as: ‘From Danny van Leeuwen, Health Hats. (including the link to my website). I welcome edits and improvements. Please let me know. danny@health-hats.com. The material on this site created by others is theirs and use follows their guidelines.

The Show

Proem

I live in a bubble. Inside the bubble, I can drop my shoulders, take deep breaths, find humor and love, and rest. I’m creative, productive, and silly. Trust soaks the peat under the moss on the floor of my bubble. I feel it squish between toes. Ahhhhh. The bubble moves with me. I can step outside the bubble; the bubble can subtly pop and explosively vanish. Indeed, when outside the bubble, I’m a bit or much more tense. I no longer feel that trust-soaked peat between my toes. These days I see, hear, and think about trust everywhere. A dial of trust overlays almost everything as if floating on the video of my mind’s eye. I see it with family, friends, work, screens, podcasts, news. I’m frightened how low the dial of trust appears most of the time. Sometimes the dial tries to break itself, rotating lower and lower.

Introducing Joy Mayer and Trusting News

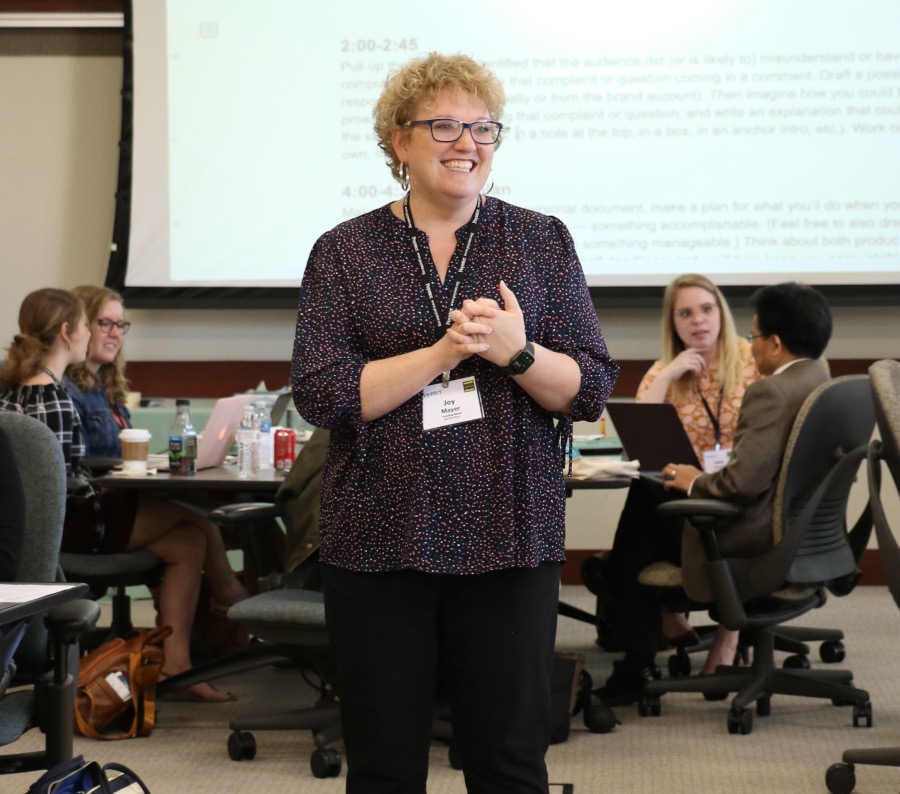

I’m a student of people, communities, leadership, health, and learning, but I’m obsessed with understanding, appreciating, strengthening trust. Goodness, Joy, I didn’t plan this introduction when we met or when we recorded. This proem, this preface, just appeared. My friend and coach, Jan Oldenburg, introduced me to Joy Mayer when I told Jan about our Safe Living in a Pandemic Initiative as my obsession with trust first bloomed. We sought expertise in trusting media. Media, where regular people seek answers to their questions about Safe Living. Joy Mayer is the director of Trusting News, a project that examines perceptions of news and trains journalists in transparency and engagement strategies. That work follows a 20-year career in newsrooms and teaching. She is an adjunct faculty member at The Poynter Institute and spent 12 years teaching at the Missouri School of Journalism. As Joy says at the end of our chat, ‘I think those of us who are asking these questions (about trust – my words) across different industries can learn a lot from each other.

Health Hats: Joy. Thank you so much for joining me. I appreciate it. I really like your work.

Joy Mayer: Thank you.

Health Hats: This whole topic of trust is never-ending, isn’t it?

Joy Mayer: Yeah. It’s complex and sticky and difficult to peel apart for sure. And therefore, super challenging and a lot of job security for people who study it. There’s just so much to look at.

Health Hats: There is. What is Trusting News?

Joy Mayer: Trusting News is a project that started relatively small, actually based on my curiosity and desire to learn more about how people decide what needs to trust. I worked for a while teaching at the Missouri School of Journalism and worked in a student-staffed newsroom there. In journalism, we call what I was doing community engagement or audience engagement. Still, my work was talking to news consumers, being the face of a newsroom, and understanding what they thought about our work. For mission-driven responsible, ethical journalism, where the journalists see themselves as really performing a public service, we should care deeply about who we aim to serve and whether we’re doing it, and what they think about our work. And so that was my job, keeping the focus of the news squarely on the people we aim to serve and being responsive to their feedback. I realized more and more that there was a basic level of distrust for too many people that prevented them from accessing what we were doing and finding it credible. When I left my job teaching there, I thought I wanted to understand more about what trust is and what journalists can do about it. How can we empower journalists to take steps to earn trust? And so what started as a part-time small research project has developed into a more extensive program

Health Hats: Is that your, like your business now?

Joy Mayer: I mean, it’s nonprofit, but yeah, that’s my full-time job. There. There are three of us on staff, and we train newsrooms and work with newsrooms individually on how to demonstrate credibility and actively earn trust.

Health Hats: So your audience are journalists, and I think you said at one point teachers. Yep.

Joy Mayer: Yep. We are a supply-side organization, not a demand side. So we work with and learn from people who work on news literacy and media literacy more generally, but our audience is not the general public. We help journalists train their audiences to be better news consumers, but we are not a direct to public operation. Our audiences are journalists.

Trust is complicated (where have we heard that before?)

Health Hats: I was listening this morning to some podcast, and somebody was going on about nobody thinks whatever. That just isn’t true. Nobody thinks that? I’m thinking, what do you mean by nobody? Does that mean you did a study, and it wasn’t 95%, so that it couldn’t be provable? What do you mean -nobody? What are you talking about? Nobody. And maybe nobody is 75%.

Joy Mayer: Not careful with our language, are we?

Health Hats: This is good that I’m talking to you. You and I met in Safe Living in a Pandemic Initiative. I would say our end-users are regular people trying to live safely in a pandemic. But like you, they’re not our audience because that’s just too big of an audience. And so more we’re about people who regular people trust, and whether they’re professionals or not, it’s those people that are our audience. But as we started trying to think about this issue of trust, we quickly realized there was no way we would be a Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval for anything. The variation and what people trust are just too monster. We didn’t have the money, the bandwidth, the interest. But we did come up with that trust occurs in a context for people. So very simply, their trust maybe about their circumstances, their personal histories, their culture. We began understanding more about people’s attitude towards individual rights and community responsibility – a continuum – and it depends where people live on that spectrum. And their risk tolerance so varies, as does their comfort with uncertainty and the strength of their critical thinking. But in a way, it isn’t trust. It’s about the world that trust lives in. Does that resonate with you? How does that figure in your work?

Joy Mayer: All of that resonates because the news landscape is very complicated. People can get information from so many sources, and the individual sort of metrics we each use to decide what is credible that’s very personal and emphasize different factors. And some of us think about that a lot. And some of us don’t think about it at all. I’m amazed by the lack of attention people pay to where this sort of spending is trusted. I think it’s helpful to think of it as a budget. Everybody trusts something, and you can spend it haphazardly, spend your trust haphazardly, and not give any thought to it. Or you can have a carefully mapped out plan. And everyone has to decide what to trust. Still, some people aren’t. By default, whatever comes at people, they decide it’s true or make a quick judgment about a whole brand or a whole source of information or a friend that they think thinks like them and chooses to trust everything from that friend.

Affective versus cognitive trust – connection or logic

All of that is true, and it’s very complicated. And one thing that we talk about a lot in our work is one straightforward way to look at trust is the difference between affective trust and cognitive trust. So, people who deal with facts like cognitive trust, that means here’s the list of why you can trust us. Here are our sources. Here is our professional credibility. Here we’re going to overwhelm you with information and give you the reasons you can trust them. But none of that makes any sense unless you have affective trust, which is, do I feel a connection to you? Do I think you haven’t yet integrity and ethics? Are you on my side or my team? Do I believe that you’re a good person or a reputable organization with a sort of affinity level of trust? And so I think that when we try to peel apart trust and just looking at some kind of list of what people bring to that. People will have different values that they bring to their decisions, and a lot of it is not articulated and not something you can talk people out of. I think those who work in trust like to believe that if we just talk enough about our credibility, we will be persuasive, and that’s just not the case.

Health Hats: So the word you use was as affective as opposed to effective? Okay. Effective. Okay. Yeah, it is interesting. The talking people out of, changing people’s minds about trust about something. First of all, I’m terrible at it, and I don’t like conflict. I’m not the guy to try to talk you out of anything. Yeah, but people try to talk me out of stuff.

Persuadable but overwhelmed

Joy Mayer: Absolutely. And so I think it’s essential to look at trust as a spectrum because some people are not persuadable. Some people are convinced that there’s a microchip in the vaccine or that everything that appears in the Washington Post must be invented or driven by a political agenda. I will never trust anything that comes from them. So if you are that committed to your mistrust, then You’re not the focus of my work. We might get there eventually. For now, I think there are many people who either make decisions very casually and don’t think about it very much, who genuinely want to consume information responsibly and aren’t sure where to trust, who are overwhelmed. All of my friends and family who email me and say Joy, is this true? Can you check this for me? Or is this an okay source? And they want to know, but it can be genuinely quite tricky to tell what the source of information is and whether it’s credible.

Engaging transparency

Health Hats: So if your audience is journalists and teachers and their audience is consumers, for those people who are susceptible to learning more about trust and their self-awareness of how they trust, what are the guideposts of that?

Joy Mayer: Our work is based on a foundation of transparency and engagement. So transparency is how do you pull back the curtain on your motivations and your processes, and your decision-making in a way that builds credibility and engagement is how do you join conversations about your work to offer a counter-narrative about it? All that starts with understanding audience feedback and misperceptions and misassumptions; if you notice that your audience thinks that you make decisions based on money, that obviously, you must cover stories that will make you a bunch of money. You’re going to sensationalized stories. We had newsrooms with people saying you’re sensationalizing the pandemic because it drives ratings. So what is your counter-narrative? So a news director comes back with a message that says that the local business market is struggling because of COVID, which affects our advertising. And our income is down this month. So we don’t have a financial incentive. That’s a counter-narrative educating people about how you operate. So we talk about what does it people think about your work and what do you wish they knew about your job? How do you take time and build into your process as a journalist what it means to tell that story? You have ethics. Is your ethics policy published? What does it cover, and how do you draw attention to it? Do you link to it from stories where you reference it? Do you talk about it on air? Do you put it in your email newsletters, or do you hope that buried on your website somewhere that people find it and take the time to consume it and understand how it relates to your day-to-day decisions?

Health Hats: Which is a microscopic number of people.

Joy Mayer: Right. Either the people who love you or hate you, probably not the busy people—just wondering how to decide when you, when they scroll through your feed, their Facebook feed and your headline is there whether it’s reputable.

Self-aware before convincing

Health Hats: Wow. This business of self-awareness to me, I don’t know why, but that really hooks me; first of all, in a way, self-awareness is just. It’s about listening, in this case, to yourself. And when you’re talking about this news manager, that’s somebody who’s listening to the consumers of news, right? That’s hard to do. You’re busy.

Joy Mayer: Yeah. I just interviewed that particular news director and about how he makes time for engagement. And he says basically that he doesn’t understand why he would be in business if he didn’t make time for it. And that some days that’s mostly what he does. And that, that is, if you want to stay in business, isn’t it worth your time to defend your reputation? The news, the local news business is not in great financial shape. They need to be worried about keeping the audience, not losing it. And if you’re losing the audience because of some fundamental misperceptions, people don’t know why there would be a paywall on a new site. People will leave comments saying you’re so greedy. Doesn’t advertising pay the bills? Why do you, why can’t, why are you even sharing the story if I can’t read it? Yeah. Do you have a counter-narrative about what percentage of your budget comes from community support? Why you rely on it? How many local people do you employ? What would happen if you didn’t do it? The fact that people get five free articles a month free, so they must care about local news if they’ve reached the paywall, right? Are all these things you can say in response? You can either see to the conversation to your critics and let them attack your integrity and the comments on a position you’re hosting. You concede it to your critics, or you can show up with a counter-narrative and be part of the conversation and correct the record. Don’t let them have the last word about your integrity.

Opinion without context. Facts with context.

Health Hats: Wow. Another thing that was important to me in my development was that there was a difference between factual and trustworthy. And since I’m involved a lot in the research community, I realized that there’s very little that’s factual compared to commentary. What do the facts mean? There’s more of it. There’s more about what the numbers mean? What is somebody laying out as a fact? What does it mean? What’s their interpretation of it? Some people don’t trust facts. My sodium is 138. But that by itself doesn’t mean anything to me. Is that a good number or a bad number? So then that’s an opinion, that’s interpretation. But, so how does that fit in this trying to manage.

Joy Mayer: It’s sometimes interpretation or opinion, and it’s sometimes just context, like for people of your age and weight or whatever, and otherwise other health conditions, let’s put that sodium number in context. It’s not your doctor in helping you interpret that is not just issuing an opinion about whether it’s good or bad. She might be trying to help you understand where it fits in and what it might mean. So same thing’s true in journalism. There are lots of ways to lie with facts. There are many ways to say here how many people are coming across the border and letting people draw their own conclusions. But suppose they lack the knowledge to say, Oh, there’s always a surge this time of year, or that was because of this bill signed by this administration or something. In that case, it can be irresponsible to put information out if people might draw the wrong conclusion, and by putting it, choosing how to put it into context is absolutely a matter of judgment. I think it might be oversimplifying to say it’s a matter of opinion. And I believe that whether you have a goal of informing people or persuading people is the real difference. Every journalist has their expertise, their perspective on the world, and there’s no way to separate us from who we are as human beings. And so absolutely you’re getting something of people’s humanity as they make decisions about what to cover and how to cover it. But I think there’s a difference between contextualizing information and opining to persuade people to believe a certain way.

Health Hats: Okay. That makes sense. Yeah. With the sodium, it could be What was it yesterday or last year. And what is it now? So it’s a difference. It’s not just a point in time. It could be a continuum. And so then it’s means something different when you look at where it’s headed or the direction it’s going or whatever.

Joy Mayer: And so your doctor, just to extend the analogy, if she wants you to walk away from that interaction, having learned something she’s going to anticipate or ask you questions enough to know what assumptions you might jump to about that sodium number. She might be thinking, Oh, we’ll test it again next year. Cause it’s never been high before. It’s probably no big deal, and you could walk away going, Oh my gosh, I’m going to die. My sodium is high. And that’s where adding that context is essential.

Now a word about our sponsor, ABRIDGE.

Use Abridge during your telehealth visit with your primary care or family doc. Put the app next to your phone or computer, push the big pink button, and record the conversation. Read the transcript or listen to clips when you get home. Check out the app at abridge.com or download it on the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. Record your health care conversations.

Earning trust even if wrong

Health Hats: So consumers of information, even though I’m, I’m up to my eyeballs in this stuff. I don’t necessarily feel that I am good at deciding whether something is trustworthy. I have certain people that I follow because I believe them. And they’ve not let me down.

Joy Mayer: They’ve shown you in the past, they’ve earned your trust in the past by giving you things that make sense to you or that are consistent with how you see something or that seem well-researched whatever your personal, that’s just being efficient to say if I’ve decided now to trust them, I don’t have to assess them every time I’ve made this decision.

Health Hats: Yeah. But then I think like in my relationship with my wife, who I’ve been, with 46-47 years, she’s almost always right. It’s just the way it is. It’s not a hundred percent. And so I still have to think in this particular circumstance, is she right? And that’s somebody I really trust.

Joy Mayer: So having a history, trusting her integrity that if she weren’t right, she would acknowledge it.

Health Hats: Yes. Oh, absolutely. Okay. Okay. That’s an important distinction, isn’t it? Yeah. Yeah. This political thing of like it’s a week to change. That is beyond bizarre to me.

Joy Mayer: And many people just aren’t. Some of that is information literacy in general. Like just understanding how research works, right? You told me this last month, and now you’re telling me this. Yes. We’ve learned things right. To findings have evolved. Yeah. And so people blame the journalist for that too, and say, you’re not skeptical enough. You’re giving us the wrong information.

Health Hats: I trust people less who aren’t willing to admit change.

Joy Mayer: Right? That is one way to look at the world. Yes. Not everyone looks at the world that way. What’s that? Not everyone likes it, though.

Rating trust

Health Hats: That’s the way I look at it. Okay. In this project, we started thinking about a trust label, and we took the model of a nutrition label. Such a nutritional label, like the sodium, the calories, the whatever, that there are facts on the nutrition label. But it doesn’t say the food tastes good or is healthy for you. And you have to draw your own conclusion based on that. And we like that model. And start thinking about if what we’re trying to do is increase people’s self-awareness about trust. Could we design a trust label? And, we came up with simple things like, can I read it? Is it a medium that’s comfortable for me? Like I’m a podcaster, but I have people who follow me who are readers. So I do both the podcast and article grade transcripts. So people who are readers can read as we talked about who wrote it. Or who spoke it, and that helps. And do they have a vested interest? Is there research behind it? And sometimes I think that’s exciting. We were trying to evolve this trust label with the idea that this could be crowdsourced like Wikipedia. On the other hand, It seems like nothing, and I know that my partner in crime, Laura Marcial, says, do you know how long it took to do a nutrition label? That was a 20 year, 30-year process. We’re on year one of trying to do something like this. If you were trying to do a trust label, like what would you put on it to help people be a bit more self-aware to help them think about trustworthiness?

Joy Mayer: It’s such a, it’s such an exciting question, and acknowledging the complexity of it off the bat and the imperfect nature of any solution is critical. Some interesting efforts within journalism include media bias charts or ratings of news brands that have a lot of research behind it. I think they are handy in plotting certain news brands on a spectrum and helping people understand that, just make some basic decisions about what to trust. I think it’s useful. The challenge is that there are so many variables and news organizations are complex. There’s a natural place for opinion journalism versus news, and you’re going to cover science differently than you cover sports. I think that assessing brands is different than assessing individual products or individual stories even. And a lot of authors are independent. So if you have a newsletter, I like how I decide whether that’s trustworthy or credible. I don’t have the shortcut there of trusting a brand. So it’s complicated. I was looking at what you sent me in terms of the nutrition label. Some pieces stuck out to me as being especially relevant for my work. I think that the question of, do they have a vested interest jumped out for me who paid for this, or what interest is behind it? What sort of influences might be behind it? Because that is probably the most common pushback of news these days because it’s driven by a political agenda or sometimes the financial agenda corporate agenda. Therefore, I don’t trust any of it or trust this brand because of who owns them or something. And, it’s interesting because journalists are very skeptical of that. The question of following the money is something you learn early in journalism school. So who paid for this research, and let’s make sure we interview somebody who didn’t benefit financially from the research because we’re assessing whether it’s credible and what the impact is. So it is reasonable as a consumer of information to say who is behind it. And in my field, there’s just a lot to pick apart there in terms of its funding. Journalists don’t talk much about where their money comes from. And it’s valid and important to ask questions about that in terms of the mission or motivation, what is the organization’s goal? What is the purpose of this piece? Do I understand whether it is designed to inform me or persuade me? Do I understand who the audience is for this publication and who they’re talking to, and whether I fit into it? Is there independence from a faction of any kind behind the work, is there is that sort of a statement of values that is there. So that’s a really interesting one to me that I think goes across many misperceptions of journalism. Is that sort of question of who’s behind it?

Health Hats: I think what I just heard you say that is missing from our label is how the piece advertises itself. Those are not the right words. But are they calling it an opinion piece or a factual piece or a story?

Transparently confusing

Joy Mayer: Huge problem. As an industry, I’m so frustrated that we are still allowing there to be so much confusion, and sometimes it’s a big problem baked into a whole product, like cable news. I can’t tell when I turn on the TV if somebody talking is paid to share their opinion or sort of analyzing or commentate, whether they’re doing straight-ahead reporting, whether someone’s even like a paid staff member or a source. Sometimes it’s tough to tell about eight people around a table. And I don’t know what I’m listening to. Versus An opinion column written for a newspaper, but and it might be labeled on the website as opinion. Still, when you paste it onto Facebook, the word opinion doesn’t appear anywhere. And so it’s all somebody sees going by in their feed is this story with this brand. And the headline is written in a way that’s clearly designed to provoke or persuade something, but that labeling doesn’t translate to all the different technical platforms. So we are allowing way too much confusion in terms of just the package we put news in and whether people know what it’s designed to do, because some people share opinions on purpose. One newsroom we were working with did a community-wide survey, and somebody wrote in and said, you need to fire your restaurant reviewer. She’s way too biased. Because they didn’t understand that, of course, the person reviewing restaurants is paid to share her opinion about the restaurants, right? That’s part of media literacy, and in my world, is this doing what it sets out to do? And is it being honest in its approach?

Person first – meeting us where we are. Where are we?

Health Hats: Yeah, trying to make complicated things simpler is a bitch. Yeah. And you think about I’m not a journalist, I’m a podcaster and, but it’s a mix of these. Some are my opinions. I try to put sources in links to more information, But you don’t know. I don’t know how people take what I say. I just think I’m little Danny van Leeuwen, and I have a big mouth. Yeah. And a lot of energy,

Joy Mayer: you can’t control what people do and what you say, but you can be aware of how you might or whether you might be accessible.

Health Hats: So how does a journalist do that?

Joy Mayer: Some of it is dependent on the brand level relationships. Why do people tune into this podcast or this TV station? What are they looking for? Are they in a hurry? Are they watching something while they cook dinner? Do they listen to this because it’s an in-depth take on a complicated topic? One note that I made with your question of, can I read it? Is it accessible to me? I was also thinking does it assume a level of knowledge that I don’t have. People are very turned off from news sometimes because Journalists often write for other nerds. And the story today about the big transportation infrastructure bill making its way through Congress is going to assume all that I’ve been following closely. So I may want that. I may just be dying for the update of what happened in committee since yesterday. Or I might be saying what’s that big thing happening in Congress right now, but I’m not paying attention to, and I might just want someone to say. Here’s what Biden proposed. Here’s what this is following up on from a campaign promise. Here are the top bullet points so that I don’t feel stupid at work when somebody mentions it. So I think people have different relationships to these sources of information, but a basic level of accessibility is this meeting me where I am on this issue.

Health Hats: Right. And it may or may not. That is not whether it’s trustworthy or not.

Joy Mayer: It’s whether it’s relevant. This is where trust means so many different things. Do I feel a connection to it? Do I trust it? Some people might mean by that is it useful? And it’s not helpful to me if I don’t understand it, or if it’s only repeating things I already know?

Health Hats: Yeah. Yeah. So what should we have talked about that we haven’t?

Joy Mayer: I think my work is based on a relentless understanding of user experience. And I think that there’s a lot that we do thinking we’re earning trust that Is not helpful or performative. Like if in a complicated story, I would like to explain why I trusted the stories involved, the sources involved in this story, and why I chose to do the story. Still, I answered those questions in a boring video that takes eight minutes to watch. That’s not helping anything because only your mom is going to watch that video. Or you have to be aware of how people are finding if everyone and your website for a piece of information and you did a story, but it had the wrong headline on it. And your search engine optimization is all wrong, and people are landing on a story from last year, at this time when they were asking a similar question, and there’s messing on that story that makes it obvious enough that it’s an old story. So you might think, look, we did our job. That’s just on them if they find the old story. There’s just a lot that gets in the way of trust those careless on our part as information providers. And so I think that question of I guess I just would put a bow on this by saying that for me, trust work has to begin by identifying the obstacles to trust what gets in the way of people finding us credible. And that is going to be different if you’re cable news or a weekly community newspaper. It’s going to be different depending on whether you have a tight geographic focus or you cover a niche topic for the world. And it’s really about just a deep understanding of what people are looking for from you and what you, what they do and don’t understand about you, and what you want them to know about you. And so there aren’t a lot of cookie-cutter solutions, but the concepts of what do you value as an organization and what value you provide? Being clear on those things. So that you, as you’re building a relationship, that’s what trust is and what sort of shared understanding and values is it based on? And that’s going to be different for different organizations.

Health Hats: That’s profound. I have to chew on that. I’m a self-centered guy, and I just apply everything to myself first. Yeah. And I think about, one of the things that I do in my My intro to my podcast, as opposed to the introduction to an episode is, I just have that I’m a two-legged, cis-gender old white man of privilege to set the context that where I’m coming from. So that, in, in 10 words or whatever that is, I’ve laid out something, and I wear all these hats, that, I have, I have different experiences, to try to give a context for whatever tumbles out of my mouth or my channel or my whatever.

Joy Mayer: That’s an integral part of a trust. One challenge is that some basic values of news can seem outdated in today’s news landscape because plenty of people will say that they prefer to get their news on YouTube and want to know who’s talking to them. They want to be able to see them. And they’re building a connection. And that person may be as honest about where they’re coming from. In the research about news consumers, we’ll see that somebody’s saying I get my information from Christian radio because at least I know where they’re coming from. I don’t mind that they have a bias and a worldview. They’re honest about it. This sense that people know that journalists are human beings and that we bring our worldview with us to the job. That’s just there’s no way around that. Some professional standards and practices keep each other accountable, and where we learned to set that aside and fill in the gaps of our own perception and understanding. But we’re still human beings. And so I think that honesty and transparency about who we are and where we’re coming from are key.

Falling off the cliff of trust

Health Hats: Anything you want to ask me?

Joy Mayer: I think that I would like to know if what that I have said does not make sense in your world. What have I said about trust that is different than how you would interpret it in your work?

Health Hats: As I said already, I think it’s the dimension of transparency that you brought out that I hadn’t thought about. Is this an opinion? Am I reporting some history? I had part of my career as director or VP of quality management in healthcare. Often I would say to my staff, or I would ask them, or I would preface what I said that this is grade C, this is grade B, this is grade Z. I have no idea what grade this is. Trying to give some context about what we know, and so I think I had a sense of that. But I don’t know that I think about that when I’m listening or reading. Obviously when I was telling you at the beginning that somebody said that zero something, I knew that was BS. That just made no sense. It was just ridiculous. How could that be?

Joy Mayer: If somebody values precision, that made you question the credibility of the overall product.

Health Hats: Yes. Maybe that’s another part. It’s another part of what you said that intrigues me is you can fall off the cliff of trust. When somebody made a mistake, they just made a mistake, and then all of a sudden you don’t trust them anymore. Yep. Wow. So

Joy Mayer: Sometimes that’s valid. Sometimes it’s a sign of a much bigger problem or sloppy work in general. And sometimes someone transposed two letters when spelling your neighbor’s kid’s name in the sports section five years ago, and you decided they must just do sloppy work in general. Yeah, it’s that is one criterion, and people put a value on different things.

Trust as digestible

Health Hats: Yeah. I think this increasing awareness about trust is honorable work. I’m delighted you’re doing it. I enjoy. I can handle it in small doses. Yeah. Cause it I feel like every time I get into something, I was going to say, it’s a rabbit hole. It’s too dramatic, but it just lays bare complexity. As if there isn’t enough complexity.

Joy Mayer: So it is vital to take complex topics and make them digestible. And so I guess that’s partly what you’re trying to do is give people things to hang on to and think about. Yeah. Yeah, but you’re right. There’s a lot to know and understand,

Health Hats: I follow Aaron Carroll as a physician at the University of Indiana. He does some great work. Oh my goodness. I forget the name of it. I’m going to have to edit in the title. Healthcare Triage I recognize him, I trust him because he tries to break down the complex, and he’ll say how confident he is of something or that it’s evolving, or I thought this is before, and I don’t believe this anymore.

Joy Mayer: That’s what we were saying earlier about valuing the idea that information could change or that not all is known. And for some people, that hinders trust cause you don’t even know what you’re talking about. And for other people, the acknowledgment that there is something not known or that this story isn’t answering all the questions or that something is more complex than you can explain in this format or whatever. For some people that, that level of transparency builds trust.

Health Hats: Yeah. Thank you. This is great. I appreciate you taking the time.

Joy Mayer: Good conversation. And I think those of us who are asking these questions across different industries can learn a lot from each other.

Health Hats: Yeah. Yeah. Good. All right. I’m sure our paths will cross again.

Joy Mayer: I hope so. Thank you.

Reflection

I love that we circled back to the metaphor of trust as digestible. I think a lot about a nutrition label of trust. I probably won’t live long enough to see that developed, tried, testing, and used.

So much tension in trust. The tension of people’s bubbles bouncing against each other as in affective versus cognitive trust, connection or logic; persuadable or cast in stone; facts, context and opinion; can we live with what we see when we learn how the sausage is made?

As a change agent, I subscribe to Deming’s theory of profound understanding. To me, it means understanding as much as you can about organizations and its people and processes and then work on change. Do I really want a profound understanding of the trust peat my toes squish in my bubble? Can’t I just enjoy it?