Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 46:22 — 42.5MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS | More

Kathleen Noonan’s quest to build bridges between communities & researchers with long-term relationships & respect for experience & expertise, just like juries.

Summary

Kathleen Noonan, the CEO, catalyzed the transformation of the Camden Coalition into a national platform for complex care. She focused on capacity building, bridging healthcare research with community organizations, and emphasizing the power of diverse partnerships. Noonan is a staunch advocate for community-driven healthcare, pushing institutions to incorporate local insights and foster long-term relationships that shape better research and policy outcomes.

Click here to view the printable newsletter with images. More readable than a transcript, which can also be found below.

Two five-minute clips on YouTube.

Contents

Episode

Proem

In 2020, early in the COVID pandemic, I joined with several colleagues asking the questions:

How can the research industry help laypeople and communities find evidence-based guidance on how to live safely? Guidance that answers their questions when needed? Guidance that feels familiar and helpful. Guidance they trust. How can we be inclusive of our communities’ awesome diversity? See the podcast episode here.

We spent several years exploring those questions, informing my passion for community-research partnerships. I highlight such partnerships as often as possible in my podcast. One of my primary advocacy goals is to promote research that answers questions the public and communities ask.

My guest today, Kathleen Noonan, is CEO of the Camden Coalition, a multidisciplinary, community-based nonprofit working to improve care for people with complex health and social needs in Camden, across New Jersey, and nationwide. They develop and test care management models and redesign systems in partnership with consumers, community members, health systems, community-based organizations, government agencies, payers, and more to achieve person-centered, equitable care.

Podcast intro

Welcome to Health Hats, the Podcast. I’m Danny van Leeuwen, a two-legged cisgender old white man of privilege who knows a little bit about a lot of healthcare and a lot about very little. We will listen and learn about what it takes to adjust to life’s realities in the awesome circus of healthcare. Let’s make some sense of all of this.

The fragility of health

Health Hats: Kathleen, thank you so much for joining us. I’ve been looking forward to this. When did you first realize health was fragile?

Kathleen Noonan: That’s a great question. There are so many different answers to that. At some point as a kid, you realize that your parents aren’t just older than you, but older adults don’t stay around. When I was a kid, there was a girl on my block who passed away from pneumonia. It was an early developmental moment. But then, when did you realize that health is fragile because the healthcare system is so fragmented? It is another whole thing. When did I realize that we make our health more fragile because of the system we’ve built?

Journey to healthcare advocacy

Health Hats: Tell us about the Camden Coalition and your path to becoming CEO of the Camden Coalition.

Kathleen Noonan: I didn’t expect to find myself in healthcare as a 20-year-old or even a 30-year-old. I started out doing children’s advocacy work after college. I was a lobbyist for a children’s advocacy organization in New York City and greatly cared about economic benefits. Some might call it economic justice now, but it was things like earned income tax credits and better wages back then. Those were not the issues I worked on. You get what you get In the children’s advocacy organization. I worked on early childhood and issues of the crack and AIDS epidemic in New York City. I learned much about government and governance, state and local roles, and the federal government’s roles.

Insights from the legal and corporate worlds

Kathleen Noonan: I went to law school and paid off my debt by working as a corporate lawyer, which was not a terrible experience. I always tell people that one of the great things about the lawyers I worked with was that they were open to two sides of a story. And I sometimes find that many people are not open to two sides, even in my peer groups.

Health Hats: If not 10.

Kathleen Noonan: Exactly. You’re so right about that. That is part of our issue. I love that these lawyers were very open to the fact that I was there to pay off my debts and would go and do something else, which I did.

Transition to Children’s Policy and Healthcare

Image by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

Kathleen Noonan: Next, I engaged in many children’s policy work – child welfare, mental health, and juvenile justice. When I landed at the Children’s Hospital in Philadelphia (CHOP), I wondered what I was doing there. Then I spent ten years learning about healthcare and learned, oh my Lord, this system is very broken.

First encounter with Camden Coalition

Health Hats: My first experience with the Camden Coalition was at last year’s annual conference. Our mutual friend, Janice Tufte, encouraged me to participate for five years, and I just kept blowing her off. I was involved in so much and didn’t need anything else on my plate. Then Janice called me and said the conference will be in Boston this year. There’s a beehive that sounds right up your alley, so I went. It was terrific.

The impact of diversity at conferences

Image by conference attendee

Health Hats: I was in awe of that. What was there? 600, 650 attendees. This was not a small conference. The attendees were young, and I pegged the average age to be 35. I made that up, but it wasn’t 60 like many conferences, and it wasn’t 12. It was a diverse audience—visibly diverse (skin color and mobility)—some newbies their employers sponsored to learn more and veterans. Veterans meant people with around ten years of experience in their organization – deep and narrow expertise, whether the unhoused or victims of violence or transportation. They were excited about what they could accomplish. I was fascinated.

Meeting of the minds over community – research interfaces

Health Hats: When we spoke recently, we found commonality in the community-research interface. The community service business and the research industrial complex have different skills. I’m in the PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Institute) world, where people are committed to investing in community research interfaces. I’m now wondering about your perspective and experience in the service, advocacy, and lobbying world with the Camden Coalition. What’s your experience?

An outsider co-directing a Research Center

Image of David Rubin, MD from https://www.research.chop.edu/people/david-rubin

Kathleen Noonan: I went to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) to be the co-director of a research center as a lawyer and policy person, not a researcher. I came in as an outsider with an outsider’s perspective. My co-director, a pediatrician researcher, David Rubin, just left CHOP to attend the University of California. He was a researcher working on issues related to under-resourced kids and families. He was frustrated that the research that he was doing wasn’t doing a damn bit of good and was willing to say that out loud, which is something that a lot of researchers aren’t willing to do. So, kudos to him.

Health Hats: He did the research, and he had promising findings.

Implementation, a different animal altogether

Kathleen Noonan: Right. The results never hit the front line in policy or program changes at the state, local, or federal government level and weren’t influential in his system. If you are at a children’s hospital researching kids in the child welfare system or the public school system in a place like Philadelphia, your research is not at the top of your mind.

Shout out to Dave Rubin again. Dave, you can thank me when I see you. He was not aggrieved but asked what we could do differently. What can I do with the levers I do have? To CHOP’s credit, they funded us to start a research center. They allowed us to use those funds to think about communication and policy differently so that we could use influence levers differently. I learned a lot about research. To answer your earlier question, I learned how long it took and how siloed it was from research to policy and vice versa.

Who asks the research questions?

Image by Rohit Farmer on Unsplash

Kathleen Noonan: The questions researchers wanted to answer were not necessarily those that policymakers, community members, or parents wanted answered. It was essential to spend time thinking about those things together. We also had to spend more time talking to policymakers and programs to do relevant research.

Partnering in the community

Kathleen Noonan: More recently, Policy Lab has done a great job partnering with community organizations. But we had to get outside the hospital. We would not expect people to come to us if we wanted to do this work. We had to go to them.

Health Hats: You had to identify community organizations that were potential partners and go there.

Kathleen Noonan: Yes. Earlier in Policy Lab’s history – history because it just had its 15th anniversary – we focused on program and policy levers. I started to partner with organizations and community organizations. They have a more robust program with an earlier goal: community partnership.

Health Hats: About policy or with legislators, council people, and another provider?

Kathleen Noonan: Administrators, other provider organizations. When we received funding for a program, we looked at a new way to treat children and adults with acting-out issues and adults with anger management issues. They need a little help to live together better. We said we’re not going to do this at CHOP. We will find community-based organizations that want to provide this service and do the project at their site, not at CHOP. But go out to community-based organizations and find them to do the programs with. So, we started that way.

Earning the right to speak

At Policy Lab, resourced by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, had communications staff and policy team members who were team members with the researchers. Researchers in a hospital are often clinicians, too. A person working on the research methods might be skilled at facilitation, communications, and policy. They are the ones who are going to go out and meet with community partners. Both come to the team with their expertise. I remember a staff person like this attending a community meeting, and we hadn’t been to these community meetings in West Philadelphia in a long

Image from the Noun Project

time. And she asked me what I thought she should say at the meeting or what do should she do. I said we haven’t earned the right to speak in these meetings yet. We’re not going to say anything. Please introduce yourself, but I don’t think we have earned the right to say anything. Why don’t we go to some meetings and listen to what they say and think about what we have to say in a few months? I think you also have to go in with that attitude.

Full of myself

Health Hats: It took my whole career to learn that. It’s a side effect of being full of yourself. Yes, I have strong arrogance muscles.

Kathleen Noonan: I get you. It’s not bad. You must learn to temper it and say, I’m sorry when there’s been too much. I get it.

Call to action

I now have one URL for all things Health Hats. https://linktr.ee/healthhats to subscribe for free or with a contribution through Patreon. You can access show notes, search the 600-plus episode archive, and link to my social media channels. Your engagement by listening, sharing, and commenting makes quite an impact. Thank you.

Punching above our weight class

Image from Openart.ai

Health Hats: You’re at the Camden Coalition, which differs significantly from CHOP.

Kathleen Noonan: Yes. I love it. We’re about 80 people. We are small but mighty, and we punch above our weight class. I spent my last two and a half years at CHOP in the C-suite and learned much about hospitals, how they operate, and what they can do well. They certainly can do many things well. Many kids and families are getting the care they need, but I also had a good sense of what they didn’t do well and what they needed community partners for. The Camden Coalition provided this opportunity to go on into the community-based side of it and say, okay, what? It also allowed me to work with a partnership, a coalition of hospitals, community-based organizations, and community residents. I have four of my trustees from my community advisory committee. I have another trustee who’s a consumer advocate. There’s just a coming together of a diverse group, and that was a different experience than I had at CHOP.

From a local to a national organization

Health Hats: The Camden Coalition is a local and national organization.

Kathleen Noonan: We started as a local organization because Jeff Brenner, our founder, was a physician who, very much like Dave Rubin, was frustrated that his work wasn’t doing a damn bit of good. That seems to be the Theme. I guess the next job I’ll get will be a doctor who comes to me and says, I feel like my work isn’t doing much good. Jeff Brenner, within the Cooper Medical System, created this model of the nurse, the social worker, and the community health worker leaving the hospital, right? That’s important – seeing clients where they were, as well as the most complex clients, with medical and social complexity. So, we did that, and we were fortunate because I know all too well that thousands of community-based organizations, such as the Camden Coalition, are doing incredible work. The fact that Atul Gawande singled us out in a New Yorker article is luck to some extent. I believe that we hold that with a lot of humility here. It allowed us to have a national point of view, which is not typical for a community-based organization. And I say again, these community-based organizations have little power, so we must use it wisely, be generous, and share it.

Kathleen Noonan: We started as a local organization because Jeff Brenner, our founder, was a physician who, very much like Dave Rubin, was frustrated that his work wasn’t doing a damn bit of good. That seems to be the Theme. I guess the next job I’ll get will be a doctor who comes to me and says, I feel like my work isn’t doing much good. Jeff Brenner, within the Cooper Medical System, created this model of the nurse, the social worker, and the community health worker leaving the hospital, right? That’s important – seeing clients where they were, as well as the most complex clients, with medical and social complexity. So, we did that, and we were fortunate because I know all too well that thousands of community-based organizations, such as the Camden Coalition, are doing incredible work. The fact that Atul Gawande singled us out in a New Yorker article is luck to some extent. I believe that we hold that with a lot of humility here. It allowed us to have a national point of view, which is not typical for a community-based organization. And I say again, these community-based organizations have little power, so we must use it wisely, be generous, and share it.

Complex care center

Through that, we started talking to other groups around the country doing the kinds of things we were doing. They were often ahead of us. We developed the idea of bringing people together in a sort of home for the field of complex care with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and AARP.

We built this national center and the conference you attended, and we wanted it to be different from the academic medical conferences I attended for ten years. I wanted it to be a little bit of that, but I didn’t want it to be all. I wanted it to be a little bit of the children’s advocacy convenings I went to in New York City, which was, sometimes, with Act Up in the room because it was the time of the AIDS crisis. Sometimes, family daycare providers filled the room. We spent much time considering the diversity of voices. You saw that in Boston. We continue to get support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation to have a national center here, too. Push out information about the field of complex care. We teach and train. We just launched a new certificate on complex care, which we hope will allow other providers to bring the diverse teams working on complex care into their program or institution, or even across programs, and for people to learn and learn together and skill up together. Watch a video about the certificate here or in the episode show notes.

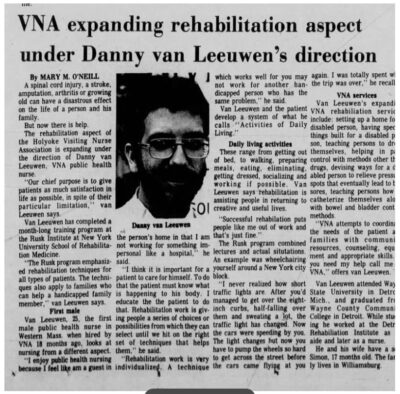

Community Nursing in 1976 – Walking Inner City route.

Article from the Holyoke Transcript-Telegram Aug 19,1977

Health Hats: Oh, I wish I had known this a long time ago. My first professional nursing job was 1976 as the first male public health nurse in Western Massachusetts. I got hired by the Holyoke Visiting Nurses Association because they were dying to hire a guy. I was a brand-new nurse. Usually, you get into home care after years in hospital nursing. I was fortunate that that was my first professional job. I ended up quickly having an inner-city walking route, and part of that was because the women didn’t want to be in the inner city. I didn’t want to drive all the time, so I said, instead of paying me gas money, buy me shoes and a backpack, and I’ll do the inner city. It was a great way to start a profession because I was out there, and it was, even all these walk-ups and people lived in some oh man, dank and dark and, and having, whether it was diabetes or paralysis and bedsores from gunshot wounds. I had good thoughts, but they were brand new, and I mostly didn’t know. I can only come to your community once a week to help you. But it would be best if you had something every day. That stuff was not organized. I operated by the seat of my pants.

Capacity to partner

Health Hats: But this business is about the capacity to partner. I want to be more involved with the communities and have co-PIs from the community. That’s not them. That’s not what they know. We want them to disseminate their results to communities and help implement them. Where’s the money going to come from?

What happens when the funding cycle ends? The problem lasts forever. When you have a problem, you must go to the people on the front line because when I was a consultant, it was a dirty secret. People would pay you to come to solve some problem. And how do you solve it? You talk to the people who work there, and they know. They’ll listen to me for a few minutes since they’re paying me a lot. I probably didn’t have an original thought; I was just a good mouthpiece. How do you balance that tension?

Long-term relationships, lean into expertise.

Image from OpenArt

Kathleen Noonan: We see a lot of requests about community participation, which seems a little unrealistic to us. I’ll put it that way. The idea is that some people are just waiting to be asked to be a co-PI, or are just waiting to learn about methods, or even signing off on your methods, which is infinitesimal. Are they right? Is it a rubber stamp? Ask them to sign off on whether they think the question is excellent, like where they have expertise. Please give them the sign-off on that. Is that as a co-PI? I don’t know. Is that just calling someone a co-director? But they’re not. You’re somebody who is the director. It just feels like it can feel not credible. We don’t want to tokenize people in any way and worry about just our own what we are not seeing or knowing about how we’re operating. But we believe in it. Longer-term relationships with consumer advocates and community members, so you know them and what they’re interested in influencing. Why are they bringing in? If they’re bringing their story, why are they bringing their story? Why are they willing to share their story if they are to advance a policy issue or a program issue? And what policy and program issues do they want to advance to change? And then what’s our responsibility to work with them to think about the change and whether they sign off on it?

Mediation

Our community advisory committee is a group of people, some of whom I’ve known for years. I’ve known since I started at the Coalition six years ago. When I came to the Coalition, the community advisory committee was very upset with the Coalition about something. I trained as a mediator, so I had mediation to do that. Just recently, I had to do mediation within the community advisory committee because we have people who have very different points of view about drug use. We have someone who believes and several people who believe that you’re not sober if you are not using heroin but you’re smoking weed. And we have some people who believe that they’re sober and they can call themselves clean if they are not shooting up but smoking weed. When I hear researchers talk about the things I want to do, I want to be able to train myself. You must have some training or somebody on your team who understands the life conflicts that may arise when you ask people in this field to work with you on a substance.

Messy and local

Health Hats: Local work is challenging, messy, and local.

Kathleen Noonan: Absolutely. That’s why I love local work. It’s why I started in children’s advocacy locally, and I love local. It works, but it is very messy.

Community participation in research – capacity building

Kathleen Noonan: You figured out how to have community-based organizations participate in research. I’ll tell you, here’s an example for research funders to think about. We just saw a call for proposals for RCTs (Randomized Control Trials). We want to do another, maybe three or four years from now. We’ve done one RTC. Do you want to do one again? We had lots of intramural money when I was at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Researchers could use the money as a rainy-day fund or a cookie jar. Researchers could request funds from those sources to prepare to apply for a research grant. We don’t have it at all. We want to send something to this request for proposals for randomized control trial funds and say we need them to prepare for a randomized control trial. That’s what you would have to do with community-based organizations, which is, say, we’re going to fund them for two to three years to get ready to do a project or to get ready to partner.

Health Hats: I can weigh how big that PCORI capacity-building bucket is. It’s a very effective bucket. Before becoming a board member, I worked on a project funded for building capacity in Boston. The paid facilitators were good. They worked hard to build a partnership with researchers and other collaborators. I was fascinated to see it from that perspective. I agree with you. As a PCORI Merit Reviewer, I observed that academic Applications were $5 less than the max. When communities led funding applications, the question was whether they could afford to do it on that budget. Because it didn’t seem like they were asking for enough – a fascinating dilemma. Could the funds go to people who aren’t going to ask for every dollar? Then, you can do more projects. On the other hand, do they have the expertise? They don’t. They’re not paying the overhead; academics have a significant overhead, but that’s not the issue.

Kathleen Noonan: I think it’s interesting, though. Interestingly, the Affordable Care Act and other healthcare mechanisms indeed hold. Payers’ health insurance companies have a 20% overhead, but we allow universities to take 60%, so there is a disparity. It’s tough to understand.

Start with the research questions asked

Image by Camylla Battani on Unsplash

Health Hats: So, if you were thinking out of this conversation about this partnering between researchers and communities, what do you think are the most critical points in your experience? What should our listeners be thinking about?

Kathleen Noonan: Researchers usually use questions they’re interested in as a starting point, but if you want to do community-informed research, you must go out and talk to people and ask if this descriptive research is fascinating. Or is this a question you know more people than I and peer-reviewed journals would be interested in?

Long-term relationships informed consumers and researchers

Kathleen Noonan: I think that’s important. If researchers haven’t asked it, then justify why and have enough of a relationship with them to bring it to them in earnest, and they come around and decide with you. That’s a good question. You’ve already done a great project right there. I think that’s important. I think it’s essential for researchers to have long-term relationships with Consumer Advocates. These are not one-time relationships but relationships where they become educated consumers.

Consider juries as an effective, diverse set of minds

Image of jury from www.rtbf.be

Kathleen Noonan: We trust, in our country, that a jury can come together without law degrees, listen to much information, and come to a reasonable conclusion. I worked in the court for two years as a law clerk, and I never found the jury to come back with a decision I disagreed with. You can bring a diverse set of minds together. Like a lot of them, even my board has consumer advocates. They don’t know everything but provide some accountability for what we do together. Suppose you commit to some consumer advocates over time. In that case, they will learn a bit about what you’re doing and become more comfortable and experienced in questioning what you’re doing and contributing to it. Think of them as a well-rounded jury. They tell you whether this is a good idea or not. That’s how we try to think about it in the longer term. It’s essential to build longer-term relationships. I do not expect to have this study; I will go out and find somebody.

Expertise versus credentials

Health Hats: What is the consumer’s point of view?

Kathleen Noonan: I don’t want to speak from that point of view per se. I wish I had one of my community advisors here with me. But I will say this: our community advisory committee was vital when we worked on Covid and were all in Covid in Camden. And we created a community ambassador program. And we did that actually because of the states. The state said they would make contact tracing jobs available to people regardless of educational status. Then, they gave the contract to our big state university, which required a BA degree. A couple of our community advisory committee members were so disappointed because they would have applied. So, we said, do not worry about it. We are creating a new position for you. We created this ambassador position, and they were paid to knock door to door and go to different places.

However, one of the things that I learned was that we shared the research studies with them. We talked about the research with them. They needed to be as educated as possible. So that they felt perfect about saying to people like, no, I looked at the research study. There were African Americans in the study, right? They understood some of the concerns and could say to people with a lot of credibility that’s not true. So, we must give community members more credit than they might sometimes get.

Health Hats: Thank you.

Kathleen Noonan: Thank you.

Reflection

This conversation hit many of my priorities. Of course, I value promoting capacity for community-research partnerships through long-term relationships. I also prize serving emerging advocates where they hang out, and respecting expertise and experience as co-equal to credentials. What a hoot to dig up the 1977 article about my naïve, prescient, 25-year-old self.

I’m going to steal Kathleen’s jury metaphor. A jury can come together without law degrees, listen to much information, and come to a reasonable conclusion. You bring a diverse set of minds together. They don’t know everything, but together, they help and provide some accountability for our actions.

Podcast Outro

I host, write, and produce Health Hats the Podcast with assistance from Kayla Nelson and Leon and Oscar van Leeuwen. Music from Joey van Leeuwen. I play Bari Sax on some episodes alone or with the Lechuga Fresca Latin Band.

I buy my hats at Salmagundi Boston. And my coffee from the Jennifer Stone Collective. Links in the show notes. I’m grateful to you who have the critical roles as listeners, readers, and watchers. Subscribe and contribute. If you like it, share it. See you around the block.

Please comment and ask questions:

- at the comment section at the bottom of the show notes

- on LinkedIn

- via email

- YouTube channel

- DM on Instagram, Twitter, TikTok to @healthhats

Production Team

- Kayla Nelson: Web and Social Media Coach, Dissemination, Help Desk

- Leon van Leeuwen: article-grade transcript editing

- Oscar van Leeuwen: video editing

- Julia Higgins: Digit marketing therapy

- Steve Heatherington: Help Desk and podcast production counseling

- Joey van Leeuwen, Drummer, Composer, and Arranger, provided the music for the intro, outro, proem, and reflection, including Moe’s Blues for Proem and Reflection and Bill Evan’s Time Remembered for on-mic clips.

Credits

I buy my hats at Salmagundi Boston. And my coffee from the Jennifer Stone Collective. I get my T-shirts at Mahogany Mommies. As mentioned in the podcast: drink water, love hard, fight racism

Inspired by and Grateful to

Rodney Elliot, Eric Kettering, Nakela Cook, Lisa Stewart, Kristin Carmen, Janice Tufte, Alexis Snyder

Links and references

Camden Coalition

Atul Gawande’s New Yorker article

CHOP Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Policy Lab

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Janice Tufte Hassanah Consulting

PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Institute)

1977 article about Danny van Leeuwen first male public health nurse in W Mass

Related episodes from Health Hats

Creative Commons Licensing

![]() This license enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms. CC BY-NC-SA includes the following elements:

This license enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms. CC BY-NC-SA includes the following elements:

BY: credit must be given to the creator. NC: Only noncommercial uses of the work are permitted.

SA: Adaptations must be shared under the same terms.

Please let me know. danny@health-hats.com. Material on this site created by others is theirs, and use follows their guidelines.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions presented in this podcast and publication are solely my responsibility and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. Danny van Leeuwen (Health Hats)