Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 40:42 — 37.3MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS | More

Aaron Carroll, CEO of Academy Health, discusses his journey to improve health systems & decision making through community engagement & repetitive communication.

Summary

Aaron Carroll, CEO of Academy Health, shares his journey, from his frustrations with the healthcare system as a pediatrician, and the role of mentorship and science communication in his career. He delves into his efforts to make complex health issues understandable to diverse audiences through various media, his role in improving health care decision making and systems, involving communities in research, and building trust through consistent and repetitive science communication. Dr. Carroll also touches on the importance of implementation science and the challenges of making research findings effective in real-world settings.

Click here to view the printable newsletter with images. More readable than a transcript, which can also be found below.

Contents

Please comment and ask questions:

- at the comment section at the bottom of the show notes

- on LinkedIn

- via email

- YouTube channel

- DM on Instagram, Twitter, TikTok to @healthhats

Production Team

- Kayla Nelson: Web and Social Media Coach, Dissemination, Help Desk

- Leon van Leeuwen: article-grade transcript editing

- Oscar van Leeuwen: video editing

- Julia Higgins: Digital marketing therapy

- Steve Heatherington: Help Desk and podcast production counseling

- Joey van Leeuwen, Drummer, Composer, and Arranger, provided the music for the intro, outro, proem, and reflection, including Moe’s Blues for Proem and Reflection and Bill Evan’s Time Remembered for on-mic clips.

Podcast episodes on YouTube from Podcast.

Inspired by and Grateful to

Seth Godin, Nakela Cook, Ann Boland, Ellen Schultz, Steve Heatherington

Links and references

Aaron Carrol: The Incidental Economist, Healthcare Triage, Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar, New York Times, Indiana University’s COVID response.

Academy Health: Academyhealth.org/Datapalooza, Communicating for Impact, community-led research grants, Health Data Leadership Institute, Dissemination Implementation Science Conference

Episode

Proem

Danny and Ann, July 3, 2024

Together for more than fifty years, my wife and I still practice communication – practice as in repetition, experimentation, and humility with two steps forward and one step back (or one forward and two back). No wonder anyone participating in healthcare continually struggles with the puzzle of communication. Just today, I texted a pharmacy about access to a critical medication with an expired prescription, tried to explain my newly diagnosed diabetes and diet choices on FaceTime with a friend, and drafted a letter about lessons learned about measurement for team members to share with our leaders. I know some master communicators: Seth Godin, Nakela Cook, my wife, Ellen Schultz, Steve Heatherington, and my guest today, Dr. Aaron Carroll, President and CEO of Academy Health. They each excel in different ways under different circumstances. I must take care to keep listening to their content and not float above and marvel at their artistry and skill.

DALL·E 2024-07-24 09.19.39 – A scene depicting various master communicators, each in their element. One is a charismatic speaker on a stage, engaging an audience

I’m delighted to have the opportunity to spend some time with Aaron Carroll and tap into the communication challenges he faces as a communicator and leader. I’ve followed him for years on his blog, The Incidental Economist, and YouTube channel, Healthcare Triage. Dr. Carroll can, has, and will impact your health.

Podcast intro

Welcome to Health Hats, the Podcast. I’m Danny van Leeuwen, a two-legged cisgender old white man of privilege who knows a little bit about a lot of healthcare and a lot about very little. We will listen and learn about what it takes to adjust to life’s realities in the awesome circus of healthcare. Let’s make some sense of all of this.

Introducing Aaron Carroll

Health Hats: Aaron, thanks for joining me. I appreciate it. I’ve been following you for a long time.

Aaron Carroll: Sure. That’s great.

Health Hats: I love your work. You’re inspiring and make complex issues understandable and entertaining. I know how challenging that is. I’m trying to connect with younger audiences since I’m an old fart and on the way out. People in advocacy and activism are younger. They don’t hang out where I hang out. I’m experimenting with hanging out in different places. That means shorter, more complicated segments, especially since I’ve added video. Although I’m mostly a one-person shop, I have people who help me, but it’s still tough. My grandkids, 16 and 13, help and advise me. It’s humbling. Anyway, I admire what you’ve done, and I’ve been following you for a long time. I’m a little nervous that you will communicate less in your new job as CEO of Academy Health.

Aaron Carroll: You’re very kind. I appreciate it.

Health is Fragile

Health Hats: When did you first realize health was fragile?

Aaron Carroll: My dad was a trauma surgeon on top of his other jobs. He was also a thoracic and general surgeon. From a young age, I knew terrible things could happen to people. Even with the sort of medicine being as advanced as it was, things could go wrong. I heard him talk about patients, what happened to them, and how hard it would sometimes be to improve their health, which certainly hit me.

And then there’s a fair amount of chronic disease in my family as well. Recognizing that even people who appeared healthy and you might not know were suffering from some chronic condition. It happens all the time. So many Americans have chronic conditions or things that go wrong with them. It happened to me, my siblings, my parents, and others. It became more apparent as I got older and went to medical school.

Writing a Prescription Isn’t Enough

Health Hats: Why don’t you tell us about yourself and your journey from Indiana University to the Academy?

Aaron Carroll: I was raised in a medically focused family, and from a young age, I always thought I wanted to be a physician. And so, even if you asked me about grade school, but indeed high school and into college, I wanted to go to medical school. I got to medical school, and everything was fine. I became a pediatrician and went off to residency. I was very frustrated and so severely that I thought about leaving the profession. I thought I’d finish residency, but I was in Seattle. I’m going to work for Microsoft or something like that. I was mainly frustrated at the healthcare system and how hard it was to get my patients what they needed. I’d spent four years training on how to take care of all kinds of stuff, but you can write a prescription. If the family doesn’t have good health insurance, they can’t afford to fill it. Even if they have health insurance, perhaps they need help to afford the deductible or the copay. Maybe they need a car to get to the pharmacy. I could talk about everything a child needed. They often needed their parents to have a job, food security, or somewhere stable. It was incredibly frustrating.

Fix it

Luckily, a couple of mentors told me I could make a career out of trying to fix the healthcare system. Sign me up for that. It sounds great. So, I stuck around Seattle for a couple extra years and became a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar. I got a master’s in health services from the University of Washington School of Public Health. I graduated and attended Indiana University (IU) as a newly minted health services researcher.

Phase one: Independent Investigator

I think of my career at IU as having about four stages. Uh, in stage one, I was a very traditional independent investigator. I did a lot of work in clinical decision support. How can we take data and evidence over here and give it to clinicians at the point of care where they need it so they can practice more evidence-based and guideline-based medicine? I did much work in medical decision-making and utility assessment to determine the most cost-effective or helpful way to practice through patients’ eyes. How do we bring data and evidence to patients, policy, and healthcare? I also did some policy work. How do we figure out how the Affordable Care Act will work?

Phase Next: Mentor, Communicator, Responder

Then, in phase two, I became interested in mentorship. I realized there’s only so much work you can do yourself. Things require teams. I convinced my chair and the whole school to develop programs to better mentor researchers in their careers. How do we take data and evidence and bring it to the practice of research so that we can do a better job in training?

But then I realized in phase three, we need to be talking to the public. It’s not enough for us to keep talking to each other. I got really into science communication. I started a blog (The Incidental Economist) in the late 2000s. It was the golden age of blogging. Everybody seemed to have a blog, and ours focused on how we bring data and evidence to healthcare reform discussions. It was when the Affordable Care Act was being debated and finally passed. That grew an audience. Eventually, I started consistently writing for mainstream media, for the New York Times, for seven or eight years. I started a YouTube show (Healthcare Triage), which is all about how we take data and evidence and bring it to the public for better discussions about health, health research, health policy, and healthcare.

After phase four, the pandemic hit, I got pulled into helping run Indiana University’s covid response. Indiana University has 110,000 or so people. It was like running a medium-sized town. We built labs. We set up public health infrastructure. We did contact tracing and isolation all around. How do we bring data and evidence to sort public health into answering this major problem?

That later transitioned into my becoming Chief Health Officer for Indiana University. We focused on mental health and several other initiatives.

Academy Health

I’d always been an Academy Health member and had known the previous President, Lisa Simpson, my entire career. I’d always considered her a mentor, and I knew that when she was stepping away. This was a real opportunity. Academy Health is all about bringing data and evidence and improving health and healthcare for all. That’s our mission. Suppose you follow the threads of all the phases of my career. In that case, they are all about how we take data and evidence and bring it to clinicians, patients, researchers, the public, legislators, policymakers, and public health to do a better job for health and healthcare.

And so, I said there would only be one or two jobs that could be a dream job. I’d love to do that someday. When this opportunity came, it was too good to pass up because our mission is to take data and evidence and bring it to improve healthcare for all.

Communicating Science to the Public Where They Are

Health Hats: Quite a story. I’m glad you’re at Academy Health. I’m also a patient and caregiver stakeholder on the Board of Governors of PCORI. Academy Health and PCORI’s work melds together. Targeting the non-medical population is so important., The PCORI Board spoke last week about how medical practice changes. It isn’t just changing practice. You could successfully change practice and still not impact what’s happening in people’s lives. I suggested that we ought to say changing practice and life.

You’ve experimented with different tools, methods, and channels—communication to the non-medical community. So, what have you learned that you’re bringing with you into your Academy Health gig?

Created by Allison Saeng on UnsplashAaron Carroll: You need to do a lot of things. Too many people think science communication is about finding that perfect soundbite, that tweet, or that TikTok that’s suddenly going to change the world, and that is not how it works. Good science communication is retail, detailed, and requires repetition. It requires the

Image by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash

building of trust. People understand where you’re coming from, why you’re saying what you’re saying, and an explanation of how it gets done. There must be two ways for people to ask questions, have them answered, and feel heard. Too much is uni-directional: just let me broadcast it to you. It also requires a bunch of different media. The same people who might read a column in the New York Times are not the same people who might read my blog, nor are they the same people who would listen to our podcast; they are not the same people who might watch our YouTube videos. Often, the content is similar, but how we give it, how much time it takes, and which of your senses you’re using differ. It’s essential to meet people where they live and where they are getting their information. Do not believe that there’s just one solution that works for everybody. It’s also essential to ask questions and listen. We regularly survey our community on their professional and personal needs, how they communicate, and how we might be better reach them. We work hard to train our members to do this better.

| Figure 4: Image by Alex Shuper on Unsplash |

The Practice of Communicating for Impact

Image by Alex Shuper on Unsplash

Our flagship online course, Communicating for Impact, is designed to address this need and covers the foundational aspects of strategic communication- Knowing your audience and crafting effective messages. Choosing the proper channels to deliver those messages is much of what I was talking about. We’ve also recently piloted another online course to address misinformation and how researchers can use communication strategies to build trust with key audiences. It is not enough to wait till something terrible happens and then post a counter. It doesn’t work. Sometimes, it doesn’t work to bring attention. Still, if you can build that crucial trust over time, you can prebut not rebut, but prebut by getting people to think better about how they take in information, to question its truthfulness and how much they should trust where they’re hearing it, and what they’re hearing. But again, that takes time and effort.

I don’t want to say it’s easy; I’ve spent 15 or 16 years with this being one of my true passions. As you practice it and do more, you get better at it. No one is born with those skills. That’s one of the things people also mistake: they think you’re born a good writer, or you’re born able to do video, or you’re born able to do podcasts. It takes time. It takes practice, just like anything.

Health Hats: I’m like you. I know there are readers, listeners, watchers, and long-form people: there’s the one-minute person, the six-minute person. My grandsons are good written word and video editors. I talk with them about the one-minute shorts on TikTok and Instagram. They’ll tell me I’m burying the lead. Don’t worry so much about the end because nobody will get to it.

Aaron Carroll: There’s wisdom in that. Even when you’re writing columns, I learned to watch my editor, every single time, take the bottom paragraph and move it to the top because we instinctively think, oh, you want it upfront.

Engaging Lived Experience

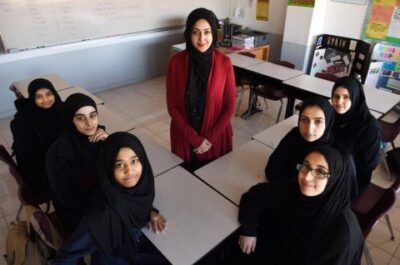

Image from https://www.pcori.org/engagement/engagement-resources/engagement-research-pcoris-foundational-expectations-partnerships

Health Hats: I wanted to talk to you about having people with lived experience from beginning to end. The nuts and bolts are challenging because people have varied skills, interests, styles, and time. We were talking about it at PCORI. We have a Methodology Committee., It bothers me that no people with lived experience are on the Methodology Committee. I had lunch with the new chair of the Committee. We talked about looking for a person who started with lived experience with chronic illness and then learned skills about statistics and research. Then, we could have a scientist who became a born-again patient. So, the lived experience came from two different directions.

Aaron Carroll: Yeah.

Patients Included at Academy Health

Health Hats: Academy Health has done much over the last few years by working with people’s lived experiences. So, what are your aspirations for this new role?

Aaron Carroll: Well, partnering with communities and those with lived experience is a priority for Academy Health. Much of what we’re trying to do is make research better. And we all know that those kinds of partnerships improve research. For instance, an Academy Health team supports ten community-led research grants. These go beyond just community engagement to community leadership. The research projects elevate community voices. And make the priorities of communities the primary goal of local health system transformation efforts. The funded studies address local healthcare, individuals, or systems. They address local healthcare system issues and importance to communities of color—people with disabilities, LGBTQ-positive individuals, and other historically marginalized populations. We proudly hold patient-included events such as the upcoming Health Datapalooza. I’m pretty sure you were a scholar at that last year. I’m sure you have a lot to contribute and talk about. That conference has met patient-included criteria since we began hosting it in 2016. We want patients involved in the design and the planning to speak and attend. We offer financial support for travel and accommodation as much as possible. We accommodate disabilities as well. It’s critical—we push the envelope there. I’ve been pleased to see that AHRQ and even the NIH are much more focused on patient-included research, not just in one phase, but trying to get people with lived experience who can contribute necessary components through research from its conception to its design to how we’re going to publish it and disseminate. It’s crucial if for no other reason it’s about building trust. It’s about creating that community so that when we finally get results and want to go out and implement them, we get the buy-in that people feel heard, trust the healthcare system or other parts of the system, and hear them.

Aaron Carroll: Well, partnering with communities and those with lived experience is a priority for Academy Health. Much of what we’re trying to do is make research better. And we all know that those kinds of partnerships improve research. For instance, an Academy Health team supports ten community-led research grants. These go beyond just community engagement to community leadership. The research projects elevate community voices. And make the priorities of communities the primary goal of local health system transformation efforts. The funded studies address local healthcare, individuals, or systems. They address local healthcare system issues and importance to communities of color—people with disabilities, LGBTQ-positive individuals, and other historically marginalized populations. We proudly hold patient-included events such as the upcoming Health Datapalooza. I’m pretty sure you were a scholar at that last year. I’m sure you have a lot to contribute and talk about. That conference has met patient-included criteria since we began hosting it in 2016. We want patients involved in the design and the planning to speak and attend. We offer financial support for travel and accommodation as much as possible. We accommodate disabilities as well. It’s critical—we push the envelope there. I’ve been pleased to see that AHRQ and even the NIH are much more focused on patient-included research, not just in one phase, but trying to get people with lived experience who can contribute necessary components through research from its conception to its design to how we’re going to publish it and disseminate. It’s crucial if for no other reason it’s about building trust. It’s about creating that community so that when we finally get results and want to go out and implement them, we get the buy-in that people feel heard, trust the healthcare system or other parts of the system, and hear them.

Call to action

I now have one URL for all things Health Hats. https://linktr.ee/healthhats. You can subscribe for free or contribute through Patreon. You can access show notes, search the 600 plus episode archive, and link to my social media channels. Your engagement by listening, sharing, liking, and commenting makes quite an impact. Thank you.

Key Points

Health Hats: So, what do you want this audience to know about you, Academy Health, or your upcoming conferences?

Lived Experience at the Table – Your Lived Experience

Aaron Carroll: We want people to be involved. We’re not just an organization of MDs and PhDs. We are an organization dedicated to using data and evidence to prove health and healthcare for all that. It necessitates having people with lived experience at the table. We’d love for people to attend our meetings. As I said before, Health Datapalooza is probably the one that focuses most on that. It’ll be in September. Registration just opened. It’s at Academyhealth.org/Datapalooza. I’m sure you can find the link attached here. Please become involved in the organization, attend the meetings, and participate.

We want those voices. A month or two ago, I was at our Health Data Leadership Institute, and there were patients and those with lived experience who sat on the panels and taught others how to do this critical work. We want to be inclusive. We are not just looking for academics. Something like just under half of our membership comes from academics.

Health Hats: That is dramatic.

Aaron Carroll: We have people come from government; people come from us, and our members come from, you know, non-profits. And for-profit corporations, they work at think tanks. Some are people like you who have lived experience and have something to contribute to that evidence base and put it into use.

Research Skepticism

Health Hats: I am a big shot at PCORI, so I’m eyeball-deep in research, not as a researcher, but I’m quite the research skeptic because I feel like I’m more than aware of what it’s not. You did a series on the research industry, which I found fascinating. One of the things that’s interesting to me about research is that I feel like implementation is local.

If you research appendectomies and antibiotics versus surgery, that’s one kind of research. But the stuff about the system and community is different. The key seems to be that somebody cares enough to dog it where they live. I’m not sure what the generalization is. How do you allocate dollars for local because that’s where the experimentation and some good ideas happen?

Learning When the Hypothesis isn’t Proven

Health Hats: Then there’s stuff that doesn’t work or get published. But if anyone is like me, I learn way more when what I tried didn’t work than when it did. I was an editor of the Journal for Healthcare Quality and on the editorial review board for about 15 years, and we tried our darnedest to get people to publish about stuff that didn’t work. We got maybe five submissions in 15 years. It was maddening.

Aaron Carroll: It is so hard, and one of the problems with how we do research is we want positive results, and all the incentives are aligned to try to make that happen. And so, people wind up, even if it’s not consciously, driving the way that they create the study, the way they design it, the way they do the analysis and the way that they talk about it, all to make everything—looking more positive leads to results that sometimes aren’t reproducible and take us down blind alleys that don’t work. It also means that we don’t learn like we should because, as you correctly noted, we learn just as much from our failures and mistakes as we do from our successes. It’s also a problem that when you do a study, it’s just a perfect, idealized, unrealistic environment.

Implementation Science

Aaron Carroll: Just because something worked in that environment doesn’t mean it will work the same in the real world. There’s a vast new branch of science called implementation science, which looks at how we accurately take this over here in research and then make it work in the real world, which is much more complicated than people think. At the end of the year, we have another conference called our Dissemination Implementation Science Conference, which focuses on that. How do we get the results out to the world so that people know about them, and then how do we correctly implement them in ways that will work?

Efficacy and Effectiveness

Aaron Carroll: We always talk about two words we throw around in science. There’s efficacy and effectiveness. Efficacy is how it works in a perfect situation. So, when the FDA approves a drug, it’s often efficacious. We know it can work in a perfect environment where you will get benefits and the harm is minimal. But if it’s too expensive, if people can’t get it, if there are shortages, or if people don’t know about it, then it’s not practical. It doesn’t work in the real world. Too often, we focus on one, ignore the other, and do so to our detriment because effectiveness is the real world. We must get much better at making those. But again, that’s all about trust, making sure people feel heard, communicating, and getting the results out there. We will then work to ensure that as they are implemented, we get the same results we think we should get based on studies in a non-real world.

Trust and Listening

Health Hats: The only thing I would challenge you about is making people feel heard. I think it’s listening. I don’t feel heard. I think we listen.

Aaron Carroll: Absolutely. Well, I say make them feel heard because listening is necessary but requires communicating back, so it’s not just my hearing you; it’s also ensuring I repeat it. So, it’s a two-way street, but I agree that listening is critical. It’s also engaging in communication.

Health Hats: I was at an event. I was talking to somebody and listening, but they stopped and said, “Is that the podcaster in you?” And I said, no, I’m just listening. This is listening to me. They were suspicious of me because I didn’t interrupt them with all my thoughts. It was more I was asking clarifying questions or saying, I think what I’m hearing is this. I was taken aback. To have this little strain of suspicion when I was actively listening. What are you going to do?

Repetition, Repetition, Repetition

Aaron Carroll: It’s funny because, when I think about our pandemic response at IU, people will talk about the labs or the tests or what we built, but I still maintain that one of the most important, successful things we did was webinars, not just every week, but sometimes multiple times a week. I’d answer the same questions repeatedly, and people would say, don’t you get frustrated? But that’s the work; it’s reiterating it back and back and back until people know that I’ve heard, and I’ve answered, and I will answer again. I will explain why, not just in one word, but try to explain it. It takes effort and time, and it can be grinding work. Please don’t take that the wrong way or that I’m upset about it. There is no quick fix; it takes repeatedly listening, processing, and talking to each other.

Health Hats: In my quality management professional days, being a group leader, often they would say, that was my idea. And I would respond, yeah, and this is a success. Somebody is selling this as their idea.

Aaron Carroll: Yep.

Health Hats: Congratulations, you did your job. This is not the kind of credit we need. Thank you very much for this. If there’s anything I can do for you, let me know.

Aaron Carroll: I appreciate that. Just stay in touch with us.

Reflection

We make many health decisions every day, both consciously and unconsciously. Some are as simple as scheduling an appointment or avoiding certain foods. However, most of our health behaviors are driven by habit and inertia. During the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, I led a group exploring people’s questions about the virus. We discovered that much of what people wanted to know wasn’t being addressed by funded research. As a member of the Board of Governors for the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), I’ve observed that the scope of patient-useful research is limited, and the implementation of results is inconsistent. These are my personal views and don’t represent PCORI’s official stance. PCORI focuses on Comparative Effectiveness Research (CER), which compares different medical treatments or practices to help patients and stakeholders make informed decisions. My experience has shown me that there’s room for improvement in making research more relevant and accessible to everyday people. My role on the Board allows me to identify small but impactful ways to influence the research industry. I’m particularly interested in research methodologies that can effectively study patient and caregiver experiences, functioning, and decision-making processes. Check the show notes for a link to an AI generated compilation of some of these methodologies.

These methodologies need to be validated and widely accepted within the research community. Organizations like Academy Health and PCORI are natural partners in this endeavor. I greatly value the work of Aaron Carroll and his team, and I appreciate the opportunity to learn from their expertise.

Podcast Outro

I host, write, and produce Health Hats the Podcast with assistance from Kayla Nelson and Leon and Oscar van Leeuwen. Music from Joey van Leeuwen. I play Bari Sax on some episodes alone or with the Lechuga Fresca Latin Band.

I’m grateful to you who have the critical roles as listeners, readers, and watchers. Subscribe and contribute. If you like it, share it. See you around the block.

Related episodes from Health Hats

Camden Coalition. The Jury’s In. Long-term Partnerships Rule

Creative Commons Licensing

![]() This license enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms. CC BY-NC-SA includes the following elements:

This license enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator. If you remix, adapt, or build upon the material, you must license the modified material under identical terms. CC BY-NC-SA includes the following elements:

BY: credit must be given to the creator. NC: Only noncommercial uses of the work are permitted.

SA: Adaptations must be shared under the same terms.

Please let me know. danny@health-hats.com. Material on this site created by others is theirs, and use follows their guidelines.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions presented in this podcast and publication are solely my responsibility and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. Danny van Leeuwen (Health Hats)

One Comment