Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 30:40 — 24.6MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Email | RSS | More

Dr. Joel Hudgins muses on up and downstream changes to Peds ED for emerging adults with mental illness. Higher numbers & acuity, too few beds, services, & staff

About the Show

Welcome to Health Hats, learning on the journey toward best health. I am Danny van Leeuwen, a two-legged, old, cisgender, white man with privilege, living in a food oasis, who can afford many hats and knows a little about a lot of healthcare and a lot about very little. Most people wear hats one at a time, but I wear them all at once. I’m the Rosetta Stone of Healthcare. We will listen and learn about what it takes to adjust to life’s realities in the awesome circus of healthcare. Let’s make some sense of all this.

We respect Listeners, Watchers, and Readers. Show Notes at the end.

Watch on YouTube

Read

The same content as the podcast, but not a verbatim transcript. A newsletter-like version with images. Could be a book chapter. download the printable transcript here

Contents

Update on Mighty Mouth Casey Quinlan. 2

Crossing the threshold into the ED. 2

Upstream and downstream issues 4

Can we really help? It takes a toll. 4

A word from our sponsor, Abridge. 5

System interventions/solutions. 5

Academic medical center versus critical access hospital 7

Proem

In this series we’ve met Emeka and Annie, two emerging adults with mental illness and Emeka’s mom, Erika. We learned about their ‘something’s wrong’ experience, finding treatment, family dynamics, and recovery. We met Matt, a high school teacher leading a student-run welcoming Ambassador program, and Dr. Bonnie, a primary care doc, managing the care of emerging adults with developing and full-blown illness with limited resources. You can see that I’m starting in the center with lived experience and spiraling out.

Photo by razvan-mirel-xhYhjMIfsq8-unsplash

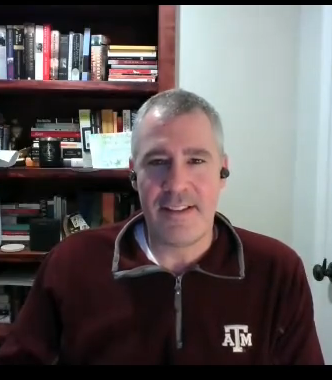

Welcome to today’s episode, #7 in the series, of the lived experience of another professional, Dr Joel Hudgins, pediatric emergency physician at Boston Children’s Hospital. Full disclosure, I worked from 2002 to 2008 at Boston Children’s leading their patient family experience initiative and I worked as a nurse/paramedic at two rural hospitals in West Virginia in the late eighties, early nineties. Despite my experience in pediatrics and emergency services, I feel out-of-touch with the dynamics of treating an increasing proportion of youth with mental illness while also faced with exploding infectious disease incidence, COVID, RSV, and flu. Emergency care and pediatrics are near and dear to my heart. Let’s see what we can learn with Dr. Joel Hudgins.

Update on Mighty Mouth Casey Quinlan

Before we begin, I published my last episode on April 1, 2023, the mashup of my chats with Casey Quinlan. Many subscribers reached out to me. Is Casey alive or has she passed? I purposefully left it ambiguous because I didn’t know when people would be reading, listening, or watching. Besides, Casey told me several times over the years when I called her about various deaths in my family, why do funerals and memorial services need to come after death? Anyway, as of today, April 12, 2023, Casey lives in a hospice, with several visitors a day, alert for short periods of time, still snarky. Go to CaringBridge.com, for up-to-date information from Jan Oldenburg.

From Health Hats, the Podcast https://health-hats.com/pod193/

Podcast intro

Welcome to Health Hats, the Podcast. I’m Danny van Leeuwen, a two-legged cisgender old white man of privilege who knows a little bit about a lot of healthcare and a lot about very little. We will listen and learn about what it takes to adjust to life’s realities in the awesome circus of healthcare. Let’s make some sense of all of this.

Health is fragile

Health Hats: Thank you so much for joining us. We need your perspective as an emergency room doc. Why don’t you introduce yourself by telling us a little about when you first realized health was fragile?

Joel Hudgins: That’s an excellent question. I grew up in rural Texas, and my granddad was a general practitioner there. I still remember going around with him back in the early eighties. He would do times where he would go to people’s homes, or he had attending privileges at various hospitals. So, I would accompany him on some of his trips. As I look back, I didn’t realize it at the time, but I think what interested me was his ability to connect with people uniquely. As part of that, you asked when I learned health was fragile. I think that was probably my exposure to sickness and people who died. I believe that relationship seemed so unique and resonated with me and was something that I think ever since I did that with him when I was young, it felt like that was the path I wanted to go down.

Crossing the threshold into the ED

Photo by Gary Lerude on Flickr/Creative Commons

Health Hats: Great. As an emergency doctor, how do people with behavioral and mental health crises come to you? What is it that you see that comes in the door?

Joel Hudgins: So, I think to answer that, you must take a little bit of a step back to where when I trained, I did my residency in Colorado and my fellowship here in Boston. We did not see this in this way at all. We certainly saw a few patients with mental health crises or behavioral health issues, but it was the minority, and I didn’t even think about it then. What we’ve seen over the last decade, but significantly ramped up in the previous four or five years, and then ramped up even more after Covid has just been teens and tweens in complete crisis—the question of why is so multifactorial. I think what we see is a cohort of patients that vary. So, you can see patients who come in that are suicidal and at high risk for suicidality, and those patients you keep in the ER until they have a place to go because they’re not safe to be at home.

Then you have patients who have behavioral dysregulation. Those may be patients who have other comorbid medical conditions or kids that may have autism, and the families are just really struggling to get the behavior under control. We see kids that come in with eating disorders that are overlaid with things like depression or suicidality. We see patients who have issues at school and feel like the school cannot handle some of their behaviors or their behaviors at home aren’t able to be addressed. We see kids with severe anxiety and TIC disorders. We’ll probably talk about the various reasons, but it does feel like the ED and the ER have become the place to coordinate a lot of the care for these kids, which is not a role we were prepared for. We’ve responded as best as possible, but that shift, or transition has happened over the last few years.

How can we help up front?

Health Hats: So, what can you do to help?

Joel Hudgins: It’s a great question, Danny. I think this is where we run into some, I don’t want to say dissatisfiers, but this is an area where I think we feel a little bit unprepared or overwhelmed. An ER is not designed for what it’s being asked to do for these patients, and that’s not the fault of the patients or the ER. It’s just a mismatch, and we’ve made solutions the best we can. And so, what we can do is, and what we’re very good at, is assessing if this patient is safe to go home. Is this patient high-risk enough to need to be kept here in the emergency room with a plan to admit them to a psychiatric facility at some point?

We’re good at that initial evaluation for patients who come in crisis for discerning. If this is a medical thing or a psychiatric problem, you know that there’s an overlay discerning the medical clearance of patients. We’re very good at that. That’s a skill that I think most emergency medicine providers have.

We’ve set up some resources for patients who leave. We’re pretty good at providing some discharge instructions for providing resources as an outpatient for connecting people to things they may not have had access to before they came to see us. We struggle when you turn the ER into more of an inpatient facility and keep behavioral or mental health patients in crisis in the emergency room for weeks. We’re just not great at that. And we’re getting better. But the reality is we’re not docs that train for that. The nurses in the ER are not nurses that came into the ER with the idea that we’re going to daily rounds on behavioral health patients. We’re going to keep them, do therapy, and titrate medications. All this stuff is not over our heads but is new to us. I think those are areas we struggle with, but there are some things we do well. But they’re usually in that upfront kind of initial evaluation part of things.

Upstream and downstream issues

Health Hats: Is the reason that people are you’re providing inpatient services in an emergency setting that there, there’s a shortage of places for people to go?

Joel Hudgins: It’s the way I think about it is it’s a little bit on both sides. So, the input to our facility has gone up. So, the number of behavioral health patients in crisis or mental health patients in crisis has increased. There’s no doubt about that. You look nationally, and that’s true across almost every pediatric hospital. So that number’s increased. Some people have argued that the severity of illness of those patients is also higher. So, things like the degree of suicidality or the degree of their crisis seem to be more than it was ten years ago or even five years ago. So that means those patients need more help and probably need an inpatient level of care more than they did in the past. The other piece of it is precisely what you said on the output side, where there are just not as many beds, and there are not as many places for these patients to go. We just don’t have the space for it. You can’t get the nurses and docs there. You can’t get enough social workers to open all the beds. So, I think there’s a dearth of rooms on the far end to get them in, to get those patients to where they need to go. And so that leaves this one place. And we are almost a holding center for those patients until those beds open, which can be weeks. And so that leaves this one place. And we are almost a holding center for those patients until those beds open, which can be weeks.

Can we really help? It takes a toll.

Health Hats: I’m thinking about being a nurse or the doc. It must be so disheartening to know what somebody needs and not be able to provide it. I remember when I’d opened my jump kit or the crash cart in my ED and paramedic days, something would be missing. Yeah. And I could deal with whatever came through the door, but when I was missing an important tool, that threw me for a loop. It seems you guys are dealing with that day in and day out, like knowing what you need to do and not having the tools to do it. That must be like, how do you stay sane?

Joel Hudgins: What you said just hit it precisely on the head, which is the thing that I don’t think we’re accounting for. At least we are now beginning to understand more about it, at least at our facility in Boston. The toll that it takes on providers is substantial. It’s precisely what you’re saying. We know we aren’t the right place for these patients. We’re not doing the best things for them, right? Nobody thinks the best thing for you if you’re suicidal is to sit in a dark ER room alone with no phone or contact for two weeks. Nobody thinks that’s the right solution.

Health Hats: Like solitary confinement.

Joel Hudgins: Yeah. It’s caught us off guard a little bit. I think we’ve tried to add some things and some therapy options, and we’re trying to do this stuff, but it’s also in the setting of you’re trying to do that amidst all these sick patients medically, who need attention and insight and all these other things.

You’re right that it takes a toll on people when you’re restraining a child. You must involuntarily give them medication or hold them down because they’re aggressive. In some ways, you’re concerned that your environment is triggering that, yet you continue to have them in that environment. That’s an upsetting thing for people. We’ve had a ton of nursing turnover, not just here nationally. And I do think this, that is part of it. I think people feel we’re not doing our best for these patients. It’s tough to be a part of that and watch it. I guess the other alternative is you can try to improve it, and that’s what we’re doing, but there’s no doubt that it sits hard with us.

A word from our sponsor, Abridge

Now a word about our sponsor, ABridge. Record your healthcare conversations with doctors and other clinicians with ABridge. Push the big pink button and record. Read the transcript or listen to clips when you get home. Check out the app at ABridge.com or download it from the Apple app store or Google play store. Let me know how it went.

System interventions/solutions

Health Hats: What are the system interventions, actions, or collaborations? What do you think would help this?

Joel Hudgins: That’s a great question, and a lot of that stuff, as you may imagine, the ER is downstream, right? So, when they get to us, in my opinion, things have already failed. I’m not saying you should view a visit to the ER as a failure, but in some ways, some kids are so severe that they need to go to the ER, but there are a lot of kids that, if they had more help upstream, things wouldn’t have ended up like this. If there were more mental health providers, if they had more accessible access to mental health providers, and if the supply was more, I think you would avoid a lot of what we see where kids end up where they are. From our standpoint, I think setting aside specific observation units solely devoted to mental and behavioral health patients where the care is standardized and the multidisciplinary aspect is crucial, where you must have psychiatrists in the emergency room. You must have mental health workers in the ER. You must have behavioral response teams in the emergency room. To be able to do all these things, you do need a dedicated space because of what I just said.

If your department’s full of insight, you will have nurses pulled for other things. For sick patients who need care right then, it’s not ideal for that. So, I think from our standpoint, we can certainly design the care model a little differently where we deliver care in a more standardized, less variable way.

And then on the other side, so that’s the input and then the ER, and then the output, it seems easy to say, and there are subtleties to this that I’m sure I don’t know. But if we could staff the beds that we do have, if there were enough reimbursement to encourage people to go into these various fields that care for these patients, then that would be a huge win. We’re trying to add physical space up here, at least to Children’s. The depressing thing is to think we’re going to add all these rooms and potential facilities, and yet, if there’s nobody to staff those things, does it matter? So certain investments need to happen because of this too. I think all three of these areas need work.

Hopeful, hopeless

Health Hats: I’m overwhelmed. It is interesting. As I told you earlier, I’ve talked to maybe a dozen people. What’s interesting so far is that speaking with people who are part of the healthcare system feels depressing and hopeless. It feels much more hopeful when I talk to people with lived experience, their parents, some of the community organizations, and some teachers who have done some inspirational stuff.

People are islands of excellent stuff. Then there is just so much that isn’t. So, the people are like, why am I doing this? Why am I Health Hats, and what do I advertise myself as? I know a little about a lot of healthcare and not a lot about that much.

Joel Hudgins: I’m an ER doc. What’s that? We know a little about a lot.

Real people all around

Health Hats: I felt that as an ER nurse. I think that I’m never really going to be a pediatric expert. I will never be a behavioral health expert, although I’ve worked chiefly administratively at Boston Children’s and in behavioral health. I’m old, and I’m at the end of my career. I’m not at the beginning or the middle. I can give it a face. These are real people this is happening to. These it’s parents, its young people, its doctors, its nurses, its people. These are real people doing real work. A better understanding of real work. So, what do you think about my audience? It is varied. Patients, caregivers, clinicians, and data geeks. So, what do you think? What advice do you offer as people struggle, learn, and advocate?

Joel Hudgins: That’s a great question. I think that is the most significant thing, and I say this because I’ve had these experiences with my family. I don’t think people understand how this affects patients, caregivers, care teams, and providers. I’ve talked to my brothers about this, and neither one is in medicine, they just have no idea. They don’t understand that in our emergency rooms, there were times in the last year when of our 45-bed main ED, 34 patients were behavioral health or psych border.

So that is a stressor. Then we’ve had record volumes with the various viruses going through, flu, RSV, and all these other than covid. We’re now funneling these huge volumes through tiny spaces. We’re creating offsite spaces to see patients not designed for emergency department care.

Profound knowledge

So, I just think until people talk about that stuff, it really, you just don’t, you don’t appreciate it or understand it. I think parents of kids, especially older kids, understand that more of this is happening, I suppose anecdotally from their children. I believe that stuff like this, where you’re talking about it and sharing people’s individual stories, is critical because nothing will change if there’s no attention to it. I’m convinced of that. I think you’re doing fantastic work just by talking about this and having a series on this, and that’s key.

In terms of other things, we’ve done a little bit of research where we’ve started to look at ED visits. We just did a paper examining whether patients are more likely to get restrained than other patients in the emergency room and how eating disorder volume has changed. This has been done, but emergency room visits for behavioral health problems show how that’s climbed and predictors of restraint use. This is still relatively new for the data geeks on the call. Even though it’s not that new anymore, there’s still room to do things around data and to show different trends and the impact of this on care.

And so that I think is critical. Then, at the provider level, I think sharing what different emergency rooms are doing to treat these patients and what care models are unique or novel in publishing those things, getting them out there so that we can learn from them. It is essential for something like this, where we’re all looking around at the right way in different hospitals to do it. Everybody does it a little bit differently. So, is there a model that works better? Disseminating that in some manner would be super helpful. Encouraging collaboration would be beneficial.

Academic medical center versus critical access hospital

Health Hats: Just think about the twelve-bed hospital where I was the emergency room nurse. I have no idea if they’re even still open. How would they be managing this insanity in central West Virginia? I can’t even imagine.

Joel Hudgins: Danny, it’s those providers that I worry about. The big pediatric hospitals. It’s a huge issue, but we have the resources to figure this out and expertise. The community ED has eight beds, and four of them are taken. They don’t have psych there. They don’t have resources. So yeah, you’re exactly right. That’s where I lose sleep, honestly, in those community emergency rooms where the care they’re being asked to provide, they’re just not equipped for.

Health Hats: Have a good holiday.

Joel Hudgins: All right, Danny, thanks a lot. It was nice to meet you.

Health Hats: Likewise. Take care.

Reflection

Photo by Luis Sánchez on Unsplash

Emergency Departments best provide temporary, front-loaded care: assessment, triage, stabilization. Move ‘em in, move ‘em out. As a paramedic/ED nurse, I appreciated the temporary nature of emergency patient/family relationships. Boarding and ongoing treatment of acutely ill people was not our forte. When I moved on to intensive care, it took some adjustment.

While I enjoyed the longer period of care, I had to draw on a different set of relationship and planning skills. Not as deep relationships as home care, but more than brief and intense in the emergency department. Dr. Joel mentioned the stress of staff unable to provide the best care they know their patients and families need.

Photo by Stormseeker on

We’ve heard this theme before during our chat with Dr. Kiame Mahaniah. I can’t help but wonder how Covid burnout combines with the increasing private equity taking over emergency department staffing impacts the treatment of emerging adults with mental illness. Perhaps we could do an episode about that in the future? Thanks to Dr. Joel for this glimpse into a day in the life of a pediatric emergency physician.

Next: Episode #8: COAST

Health Hats: Our next, eighth, episode in the Emerging Adults with Mental Illness, will feature COAST, Coordinated Opioid and Stimulant Treatment, a network of specialists to provide prevention, treatment, and recovery services instantaneously.

Dorothy Cuccinelli: We cover the eight counties in that region, so to the Massachusetts border and west, and then up north to what’s called the North Country, to the Adirondacks and south to the Catskills. It’s a big geographic area with quite a mix of demographics, everything from people in the cities to very rural locations. One of the challenges we’ve been able to meet successfully is establishing ways for people to access this program regardless of where they live.

Photo from https://cbhnetwork.com/coast

It’s unique in the sense that, as Kelly just said, it’s a phone line so people can call this number 24/7 365. They are connected immediately with a prescriber, someone who can write a prescription and get that person connected to medication assisted treatment right away. The prescription goes to the pharmacy. If the person doesn’t have the means to pay for that medication, our grant program also covers that. We can even arrange for transportation to get the prescription to that person. We use the term wraparound services a lot in the mental health field because it covers a lot of different bases that individually sometimes aren’t there. And if any one of those pieces are not in place, the whole thing doesn’t work.

Podcast Outro

I host, write, edit, engineer, and produce Health Hats, the Podcast. Kayla Nelson provides website and social media consultation and manages dissemination. Leon van Leeuwen edits the article-grade transcript. Joey van Leeuwen supplies musical support, especially for the podcast intro and outro. I play bari sax on some episodes alone or with the Lechuga Fresca Latin Band. I’m grateful to you, who have the most critical roles as listeners, readers, and watchers. See the show notes, previous podcasts, and other resources through my website, www.health-hats.com, and YouTube channel. Please subscribe and contribute. If you like it, share it. See you around the block.

download the printable transcript here

Episode Notes

Please comment and ask questions

- at the comment section at the bottom of the show notes

- on LinkedIn

- via email

- YouTube channel

- DM on Instagram, Twitter, Mastadon to @healthhats

Credits

Music on intro and outro by permission from Joey van Leeuwen, Drummer, Composer, and Arranger including Moe’s Blues for Proem and Reflection

Web and Social Media Coach, Dissemination Kayla Nelson @lifeoflesion

Leon van Leeuwen edits the article-grade transcript.

Intro photo of Vulture Couple by Rich Rieger used with permission

Photo of spiral by Razvan Mirel on Unsplash

Photo of ED by Luis Sánchez on Unsplash

Photo of ICU sign by Nicholas Bartos on Unsplash

Photo of burnout by Stormseeker on Unsplash

The views and opinions presented in this podcast and publication are solely my responsibility and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute® (PCORI®), its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee. Danny van Leeuwen (Health Hats)

Sponsored by Abridge

Inspired by and grateful to Dick Argys, Jan Oldenburg, Casey Quinlan, Dorothy Cucinelli, Kiame Mahaniah

Links

Go to CaringBridge.com, for up-to-date information on Casey Quinlan from Jan Oldenburg

Dr. Joel Hudgins, Boston Children’s Hospital

increasing private equity taking over emergency department staffing

Related podcasts

Series: Pediatric Transition to Adult Care | Danny van Leeuwen Health Hats (health-hats.com)

Creative Commons Licensing

The material found on this website created by me is Open Source and licensed under Creative Commons Attribution. Anyone may use the material (written, audio, or video) freely at no charge. Please cite the source as: ‘From Danny van Leeuwen, Health Hats. (including the link to my website). I welcome edits and improvements. Please let me know. danny@health-hats.com. The material on this site created by others is theirs and use follows their guidelines.